The Scientific Revolution

Astronomy and Physics

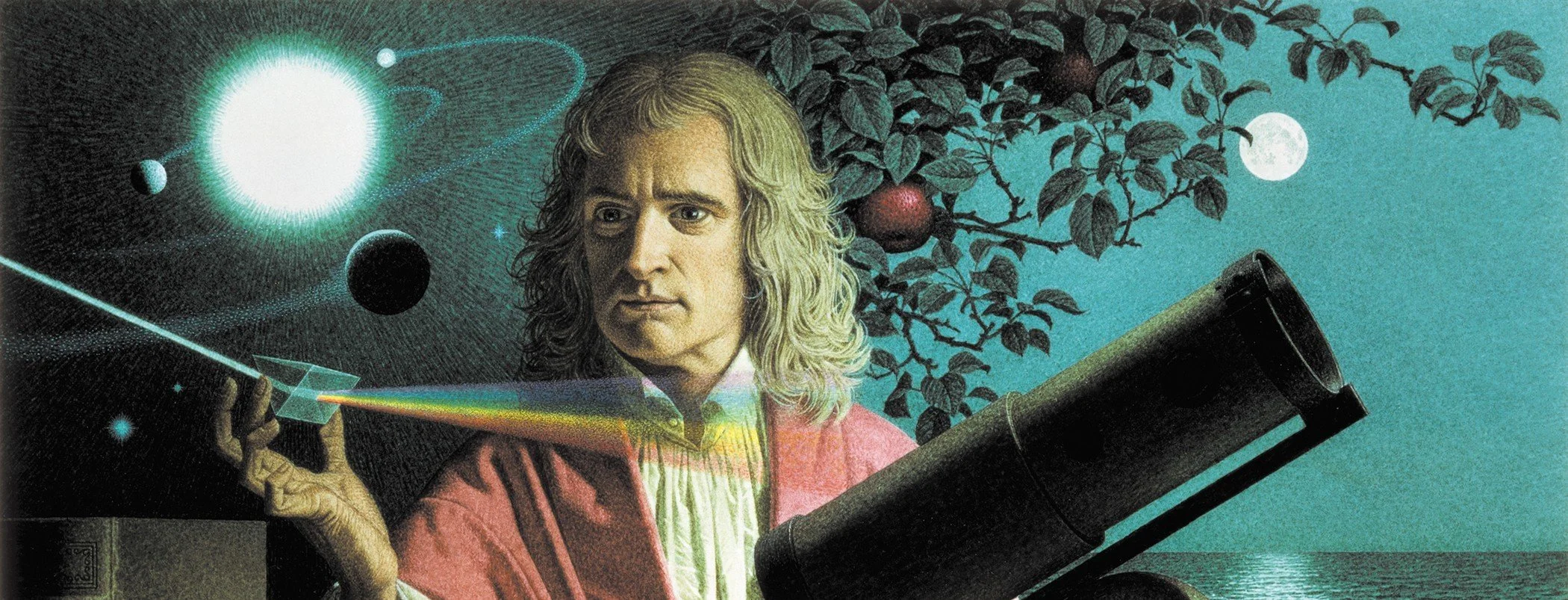

During the Scientific Revolution, major breakthroughs in astronomy and physics changed our view of the universe. For centuries, people accepted the geocentric theory, which proposed that Earth sat unmoving at the center of the universe. This idea, supported by the Greek philosopher Aristotle and later by Ptolemy, aligned with church teachings and remained largely unquestioned until the early 1500s. However, curiosity and careful observation began to challenge this ancient view.

Nicolaus Copernicus, a Polish astronomer, introduced the heliocentric theory, suggesting that the sun, not Earth, was at the center of the universe. Copernicus spent 25 years studying planetary movements and concluded that Earth and other planets revolved around the sun. In 1543, he published On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Bodies, which outlined his theory. While Copernicus’s ideas went largely unnoticed at first, his heliocentric theory laid a foundation for future astronomers.

In Denmark, the astronomer Tycho Brahe built on Copernicus’s work. He meticulously recorded the positions of the planets over many years to create precise data that paved the way for the next advance. Brahe’s assistant, the German mathematician Johannes Kepler, analyzed this data and formulated three laws of planetary motion. Kepler showed that planets orbit the sun in elliptical paths, not perfect circles as previously thought. His laws provided mathematical proof that Copernicus’s heliocentric theory was correct.

Around the same time, Italian scientist Galileo Galilei made several groundbreaking discoveries. Using a telescope he built in 1609, Galileo observed the moons of Jupiter, the rough surface of Earth’s moon, and sunspots, all of which challenged the belief in perfect, unchanging celestial bodies. In 1610, he published The Starry Messenger, describing his observations that supported Copernicus’s heliocentric view. These findings alarmed the Catholic Church, which viewed Galileo’s work as heretical. In 1633, he was tried by the Inquisition and forced to recant his views, spending the remainder of his life under house arrest.